- Home

- Jennifer Woodlief

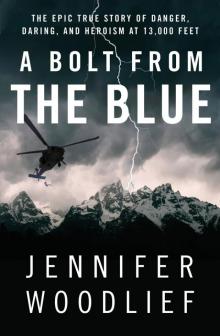

A Bolt from the Blue Page 8

A Bolt from the Blue Read online

Page 8

The rangers spent the night keeping Leo alive, although most of them later admitted that they were surprised that he was still breathing in the morning. He had almost bled out in the night, losing more than two liters of blood from his leg. The rescuers spent the day executing another series of lowerings, descending nearly 1,000 feet of dense and hazardous alpine terrain with Leo in a litter until they finally reached a promontory ledge that the pilot deemed safe enough for pickup.

Leo was hoisted off the mountain that afternoon and flown to Jackson, home of some of the world’s best orthopedic surgeons, thanks to lots of practice from all of the skiing and climbing accidents in the area. His systems were shutting down by that point, his body crashing. While inserting a rod into his femur and generally putting him back together again, the doctors told him that had he remained on the mountain, he would have survived only a couple of hours more at most.

Leo’s girlfriend Helen was at his bedside at the hospital. They had met while he was a student at Humboldt State and she was an instructor there teaching in a technical writing program. He was introduced to her by his roommate, who assured Leo that although she was not a climber, she was at least out-doorsy, a fact borne out by the pile of Outside and Backpacker magazines that Leo saw stacked up at her place.

It was while Helen was emptying Leo’s pee jars and brushing his hair in the hospital that she declared that the level of caretaking had reached a point where they might as well get married. Leo’s accident happened in August; they were married in December of that year.

Within the realm of climbing, Leo had witnessed tragedy, including watching a friend die in front of him. Intellectually, he knew that everything might be going along just fine and that the mountains could then take someone in a heartbeat. Even so, Leo’s own accident was life-altering for him.

He had imagined himself invincible, but this crisis forced him both to shift that perspective and to realize that he was responsible for putting himself in danger’s way. Most climbers assign a fairly high percentage of climbing ability to nonphysical aspects; Leo’s opinion is that the pursuit is 95 percent mental.

The stakes are infinitely high if a climber lacks confidence in himself and is out on the mountain without the right mindset. When Leo first returned to Jenny Lake, he underwent plenty of physical rehabilitation, but he continued to endure emotional trauma that often prevented him from feeling that he was present. It took him most of the next season to get back into shape, physically and psychologically. For most of that time, when he would hear rockfall—or jets, which sound like rockfall—he would run for cover. Even a decade later, while Leo was helping to chip a dead climber out of the frozen snow in the Black Ice Couloir, he suffered a flashback when someone yelled, “Rock!”

Growing up in Hesperia in the upper Mojave Desert, Leo had long identified with the outdoors and mountaineering, and he had quickly found that alpine climbing took him to the places he wanted to go. He began climbing in a gym, then quickly transitioned to climbing in Joshua Tree in Southern California, belaying off the bumper of his car. That type of controlled environment, where he didn’t necessarily have to commit to the route, actually allowed him to gain more experience. He got out on the mountains even in unsettled weather, knowing that if rain or wind moved in, he could simply rappel one or two pitches and safely return to his car.

While in college, Leo applied for a summer job with the National Park System, filling out a blanket application that did not specify a particular type of employment. In the summer of 1977, at age 19, Leo was hired to work on a trail crew, and by the end of the season, he was offered a job climbing the following summer. Initially, he saw the opportunity as a way to make his college friends jealous by meshing a hobby he was crazy about with his need for summer employment.

Leo graduated from college with a degree in resource management and interpretation and went on to get a master’s degree in environmental education, neither of which, he freely admits, was essential to his climbing-ranger career. He did teach a rescue class at Humboldt, however, with practical instruction on issues such as raising systems and how to construct a litter with rope. Despite consistently maintaining the belief that the seasonal ranger position is designed for the stage in life when a person is working summers while in college, Leo nonetheless ended up working as a seasonal Jenny Lake climbing ranger for decades.

While climbing had been of crucial importance to Leo in his early 20s, it became less so after his accident. Although he no longer necessarily possessed the same fervent climbing drive as some of the other Jenny Lakers, he did regain his self-motivation, his belief in himself. He thrived on high-risk missions when called upon to do rescue work, but he also believed that it was his duty to become a well-rounded ranger. To that end, he revisited his educational pursuits, focusing on resource work such as mapping out trails, monitoring erosion patterns, and exploring all of the lakes and canyons in the backcountry.

Leo managed to parlay this interest into outside employment by starting (with his wife, Helen) Earthwalk Press, a printing company that produces mostly topographical maps. The epicenter of the business was Jackson, where Leo and Helen crammed a 15-by-25-foot locker full of publications. The company was seasonally cyclical, with projects in the winter, sales in summer months, marketing and shipping in the shoulder seasons.

Despite the success of his nonranger job, Leo’s position at Jenny Lake was paramount, and he never failed to approach it by embracing his own personal perspective. Having faced rescue firsthand as a patient, he held a deeper understanding of the experience as well as a profound appreciation of lifesaving heroics. He was fully aware that every other national park was envious of the rescue program at Jenny Lake, and he firmly believed that he would not be alive if his accident had occurred elsewhere.

Since the time of Leo’s accident, the search-and-rescue principles of locate, access, stabilize, and transport have evolved rapidly. If Leo’s calamity in the Black Ice Couloir had happened in 2003, the rescue would have taken a couple of hours instead of two days. Less than a quarter-century after Leo’s accident, a dedicated helicopter was more or less at the Jenny Lake rangers’ beck and call, flown by an expert pilot familiar with mountain terrain and altitude. By employing advances in technology, chief among them cell phones and helicopters, the Jenny Lake climbing rangers have seriously revolutionized and refined mountain rescue.

There are other tales of Teton rescues, ones less close to home than several rangers saving one of their own in the Black Ice Couloir. Three in particular, all on the North Face of the Grand, all of which resulted in the rangers receiving Department of Interior Valor Awards for their bravery, demonstrate just how far mountain rescues have progressed.

The North Face of the Grand has long been considered a huge and punishing climb, with a 2,500-foot icy glacier, many technical sections, snowy ledges, and a hazardous route at the top. The face is easily recognizable to climbers as the logo of the American Alpine Club. Dick Emerson, one of the original Jenny Lake rangers, led the first pendulum pitch of the Direct North Face in 1953. In those days, the climb, viewed as both mysterious and devastating, was a true test of mountaineering skills, one only attempted by bold and experienced climbers. The early rangers knew that an elaborate rescue on the inaccessible face was inevitable, as bad weather or even a minor injury on that route would likely be catastrophic.

The first climbing disaster on the North Face occurred in 1967, about two-thirds of the way up, when a climber being belayed by his girlfriend was struck by rockfall that crushed his leg. Although both climbers were technically skilled, they were nonetheless trapped in unfamiliar and remote terrain with no easy way off.

The reporting of the accident alone took close to half a day, from the afternoon when it happened until after 1:00 A.M., when other climbers who had heard the couple’s screams for help alerted the rangers. As it turned out, that delay paled in comparison with the incredibly time-consuming ordeal of extricating the wounded climber.

In the 1967 operation, the rangers were ferried to the Lower Saddle, then climbed up the back side, carrying all of their rescue equipment on their backs. Seven rangers were involved in the rescue, a dream team of 1960s climbing rangers. Ted Wilson, Ralph Tingey, Rick Reese, Pete Sinclair, and Mike Ermath traversed the entire mountain to reach the scene, meeting up with Leigh Ortenburger and Bob Irvine, who had ascended from the south side. All seven of them had climbed the North Face previously, and Ortenburger in particular (author, with Renny Jackson, of A Climber’s Guide to the Teton Range) had a meticulous knowledge of the topography.

The exhausted female climber was roped up and brought off the mountain with the assistance of four rangers the day after the accident, but the rescuers knew that an attempt to carry the injured male climber, with his smashed, bleeding leg, on one of their backs would kill him or all of them. They provided basic medical care—an inflatable splint—for the climber’s protruding broken bone and radioed for morphine, a litter, more ropes, and a 325-foot steel cable with a lowering drum that they could anchor to the mountain.

Pain management consisted of a ranger flying overhead in a helicopter the next morning, nearly two days after the accident, to toss a packet of morphine down to the scene. The victim’s location did not allow the rangers to hoist him up the mountain, so instead, they had to lower his litter laboriously 1,600 feet straight down, an inch at a time, a perilous undertaking that involved repeatedly ducking rock showers as they worked. Several rangers ended up spending two nights, with little food or rest, tied to various points on the cliff with the injured climber. Ultimately, the climber was saved, but between the delayed notification and the lengthy rescue efforts, it took four days for him to travel from accident to hospital.

Rescue techniques had advanced by the time of a second significant rescue on the North Face during a late-August storm in 1980, when excessive snowfall had caused the face to ice up. The rangers initially received a report of an overdue climbing party and headed up to investigate. At the first ledge, the rangers were able to make voice contact and determined that some members of the climbing party had retreated, but two of them had continued their ascent.

At that time, there was no exclusive-use contract with a helicopter, so the rangers were forced to call on the nearest helicopter service for help. They were stuck with whatever pilot was available, without having worked with him, without knowing if he even had any mountain experience. The helicopter that was sent to them was an Alouette, a light-utility aircraft most commonly used in military operations overseas.

The rangers realized the level of danger they were asking the pilot to accept by carrying three of them with gear into the snowstorm. The pilot hovered near the sheer face, bailing once but then returning, gathering the courage needed to hold the helicopter steady enough to allow the rangers to step out onto the mountain. Once on-scene, the rangers spent the rest of the night on the face, tucked into a cave, to wait out the squall. The next morning, they decided on a place to lower the patient for aerial pickup. The helicopter used a painstaking winch system to extract the climber, which involved spinning him in midair over treacherous terrain for several agonizing minutes. Still, the rangers completed the actual extraction process of the rescue, an endeavor that likely would have taken several days in the past, in less than six hours.

A third classic operation shows the extent to which mountain rescues had advanced by the turn of the century. In 2002, rangers were inserted on the North Face to respond to an unconscious climber who had been hit by a rock and suffered a head injury. They had received a cell-phone call for help from his partner, so they were aware of the accident almost immediately. At 16 years into the short-haul program, the rangers had both a contract with a helicopter company and an established relationship with a pilot. The pilot happened to be Laurence Perry, a man whom the rangers had trained and worked with extensively and trusted implicitly. The insertion was especially tricky given the continual amount of rockfall, and it required an immense amount of cooperation between rangers and pilot, but in the end, an event that was nothing short of dazzling came off as almost routine. Laurence found a landing spot on Teton Glacier, and the short-haul was completed quickly and cleanly.

Before the use of cell phones, if a climber was injured in the mountains, the only way for his or her partner to summon help was by yelling (an option with a low probability of success) or by climbing or running back down the slope (often quite a protracted process). It usually took hours for the rangers to hear about an accident.

Initially, only a few climbers brought cell phones into the backcountry, as service wasn’t reliable and early cell phones were heavy. The first phone call from a mountain in the Tetons was placed in the summer of 1994 to report a fall on the Exum Ridge of the Grand. Within five years or so of that incident, climbers began carrying cell phones fairly regularly.

From the rangers’ perspective, the downside of a proliferation of cell phones on the mountain is that they can create a false sense of security. The concern is that climbers may rely less on basic mountaineering skills and judgment if they have a cell phone with them as backup. Most rangers will admit that the widespread use of cell phones cuts both ways, and they sometimes wish that certain climbers and hikers didn’t have the means to ask the rangers nonurgent questions at 3:00 A.M. Still, it is clear that cell phones in the backcountry have become a major lifesaving tool.

In the past, by the time rangers arrived at an accident scene, the injured person had usually either already died or was unlikely to do so. That dynamic has been nearly obliterated with the combination of cell phones and helicopters. Once rangers began to reach victims while medical aid was still critical, it was much more possible for patients to die on them after their arrival on-scene—or, to look at it another way, the rangers had a much greater chance to actually save lives.

As a result of the increased need for emergency medical training, every climbing ranger began to achieve the equivalent of first-responder status, enabling all of them to provide basic medical care in the backcountry. In addition, some of the Jenny Lake rangers became advance-life responders, meaning that they could set up IVs, administer medication, and provide oxygen to patients.

As comprehensive as it was, the advanced medical training did not envision a scenario in which a ranger would be forced to dispense medical care while suspended from the end of a rope, and therefore, the classes did not offer anything in the way of practical guidance or instruction in how to handle such a scenario. Without classroom preparation or in-field experience to fall back on, on July 26, 2003, the rangers simply had to improvise on the fly.

SIX

“I like the pilot to know that I’m Jane’s dad.”

—

Renny Jackson, head Jenny Lake ranger

As Laurence Perry ascended with Leo swaying underneath, the wind began to reach a howling sort of crescendo. Between the swirling current and the necessity of flying in tight proximity to the mountain face, Laurence was concerned about a sudden massive updraft. The problem with wind, from a helicopter pilot’s perspective, was that a pilot couldn’t react to it until he was actually getting hammered by it. Laurence didn’t want to deposit Leo on the landing site and have him halfway unclipped only to smash him into the side of the mountain.

Even more significant weather-wise, a cloud seemed to be forming on the western edge of the mountain and wrapping its way over the Exum Ridge, posing a potential threat to Laurence’s visibility.

* * *

For an injured victim in Grand Teton National Park, there can be no sound more visceral than that of rotor blades slicing the air. The first time a helicopter was used in a Tetons rescue was in 1960, for the body recovery of the only ranger fatality in the history of the park. Helicopters were first operated in mountain rescues in the 1960s, initially just as reconnaissance missions—locating victims and helping rangers asses the extent of their injuries—then, several years later, actually landing at sites

on the mountain and picking up injured climbers.

Still, in the first decade or so that mountain operations used helicopters, rangers continued to have to use valuable rescue hours climbing or hiking to accident scenes, severely cutting into the victims’ chances of survival. In order to reach someone on the Exum Ridge, for example, nearly a dozen rangers would first spend time climbing to the victim, then take additional hours to lower the patient to a site where a helicopter could safely land. In addition, for decades, Grand Teton National Park did not have a full-time helicopter dedicated to rescues, and the rangers often had to scramble around to borrow an aircraft from local scenic-tour operators.

In time, more powerful helicopters, summoned from Air Force bases in neighboring states, as well as techniques copied from the military and the logging industry, led to long-line lifting and load dropping and rescuers rappelling from the open doors of the helicopters. Beginning in the mid-1970s, in situations where there was no safe place to land a helicopter near an accident site, pilots began inserting rangers (and their gear, including litters) and extracting patients directly into and out of a scene. Initially, the three most commonly used techniques—hoist operations, fast-rope insertion, and heli-rappel—dramatically altered rescue missions in the Tetons.

The most recognizable method is a hoist operation, as depicted in the movie The Perfect Storm, when passengers jumped off a sailboat, climbed into a rescue basket, and were raised into a helicopter. In 1983, Jenny Lake rangers summoned a huge Air Force Chinook chopper to rescue an injured Exum guide who had fallen more than 80 feet on the Jensen Ridge route on Symmetry Spire. Rangers lowered a cable to him from the helicopter and winched him up into the aircraft, saving his legs and likely his life.

A Bolt from the Blue

A Bolt from the Blue