- Home

- Jennifer Woodlief

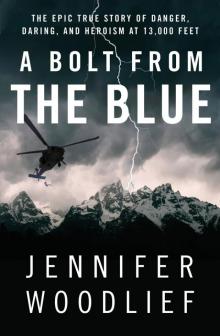

A Bolt from the Blue

A Bolt from the Blue Read online

FIVE INJURED CLIMBERS. TEN SEASONED RANGERS. ONE IMPOSSIBLE RESCUE.

On the afternoon of July 26, 2003, six vacationing mountain climbers ascended the peak of the Grand Teton in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Rain and colliding air currents blew in, and soon a massive electrical charge began to build. As the group began to retreat from its location, a colossal lightning bolt struck and pounded through the body of every climber. One of the six died instantly, one lay critically injured next to her body, and four dangled perilously into the chasm below.

In riveting, page-turning prose, veteran journalist Jennifer Woodlief tells the story of the climb, the arrival of the storm, and the unprecedented rescue by the Jenny Lake Rangers, one of the most experienced climbing search-and-rescue teams in the country. Against the dramatic landscape of the Teton Range, Woodlief brings to life the grueling task of the rangers, a band of colorful characters who tackle one of the riskiest, most physically demanding jobs in the world. By turns terrifying and exhilarating, A Bolt from the Blue is both a testament to human courage and an astonishing journey into one of history’s most dangerous mountain rescues.

Praise for A Wall of White by Jennifer Woodlief

“A triumph of storytelling. Books of this nature are automatically compared to the works of Sebastian Junger and Jon Krakauer, but in this case the comparison is apt . . . compelling, dramatic, and haunting.”

—Booklist (starred review)

JENNIFER WOODLIEF is a former reporter for Sports Illustrated and the author of A Wall of White. A graduate of Stanford University and UCLA School of Law, she has prosecuted first-degree murder cases as a district attorney and worked as a case officer with a top secret clearance for the CIA. She lives in Belvedere, California.

MEET THE AUTHORS, WATCH VIDEOS AND MORE AT

SimonandSchuster.com

THE SOURCE FOR READING GROUPS

Facebook.com/AtriaBooks Twitter.com/AtriaBooks

COVER DESIGN BY RICHARD YOO • COVER PHOTO OF MOUNTAIN BY WILLARD CLAY, PHOTO OF HELICOPTER BY STOCKTREK, PHOTO OF LIGHTNING BY MANGIWAU, AUTHOR IMAGE BY HYLA MOLANDER

A BOLT FROM

THE BLUE

ALSO BY JENNIFER WOODLIEF

A Wall of White

Ski to Die

Thank you for purchasing this Atria Books eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Atria Books and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

ATRIA PAPERBACK

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright © 2012 by Jennifer Woodlief

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Atria Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Atria Paperback edition June 2012

ATRIA PAPERBACK and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Woodlief, Jennifer.

A bolt from the blue : the epic true story of danger, daring, and heroism at 13,000 feet / by Jennifer Woodlief.

p. cm.

1. Mountaineering expeditions—Grand Teton National Park. 2. Mountaineering accidents—Wyoming—Grand Teton National Park. 3. Mountaineering—Search and rescue operations—Wyoming—Grand Teton National Park. I. Title.

GV199.42.W82G739 2012

796.52209787’55—dc23

2012012148

ISBN 978–1–4516–0708–6

ISBN 978–1–4516–0709–3 (eBook)

To Nick,

for both the climb and the view

CONTENTS

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Acknowledgments

Photographs

CAST OF CHARACTERS

Jenny Lake Climbing Rangers

Renny Jackson—head ranger, spotter (in helicopter)

Brandon Torres—incident commander (in rescue cache)

Leo Larson—operations chief (upper scene)

Dan Burgette—medic (lower scene)

Jim Springer—leader (lower scene)

Jack McConnell—at lower scene

Chris Harder (of Gros Ventre subdistrict)—at lower scene

Craig Holm—medic (upper scene)

George Montopoli—at upper scene

Marty Vidak—at upper scene

Helicopter Rescue Pilots

Laurence Perry—2LM

Rick Harmon—4HP

Idaho Climbing Party

Rob Thomas—trip leader, son of Bob, brother of Justin, stepbrother of Reese

Justin Thomas—son of Bob, brother of Rob, stepbrother of Reese

Bob Thomas—father of Rob and Justin, stepfather of Reese

Sherika Thomas—wife of Rob

Steve Oler—father of Sherika

Clint Summers—husband of Erica, Melaleuca employee

Erica Summers—wife of Clint

Rod Liberal—Melaleuca employee

Jake Bancroft—Melaleuca employee

Reagan Lembke—Melaleuca employee

Dave Jordan—friend of Rob

Reese Jackson—stepson of Bob, stepbrother of Rob and Justin

Kip Merrill—friend of Reese

ONE

“But mountains do not bow to hopes; mountains destroy those who have nothing left but hopes.”

—

Pete Sinclair, former Jenny Lake ranger and author of We Aspired: The Last Innocent Americans

There appeared to be a slight break in the thunderstorm as the pilot approached the summit of the Grand, but high winds continued to swirl the clouds beneath the helicopter, and the sky was darkening off to the west. The aircraft was a Bell 406 Long Ranger L-IV high altitude, meaning that the innards of a Jet Ranger were boosted with a bit more horsepower and the tail rotor enlarged, approximately a $100,000 conversion. The modification gave the pilot more grip at altitude. Few helicopters are able to operate at 14,000 feet, much less with an increased pay-load capacity—this particular ship was a special piece of equipment, and quite the secret weapon in terms of mountain rescue.

Helicopter N772LM, nicknamed Two-Lima Mike for its call letters, was flown by Laurence Perry, a dashing 50-year-old Brit renowned as much for his flippant attitude on the approach to an accident site as his proficiency at shutting the joking down cold once he arrived on-scene. As one of the few pilots in the world capable of passing the flying exam required by the Jenny Lake rangers—a test that required, in part, a pilot to hold a nearly dead hover for two minutes straight while balancing a 200-pound log on the end of a 100-foot rope—Laurence’s eccentricities were roundly accepted.

In more than 18,000 flight hours, Laurence had never operated a helicopter exactly like this one before arriving in the Tetons, but he had become comfortable flying it on rescue operations with the Jenny Lake climbin

g rangers in the past couple of years. In reality, Laurence could be trusted, and was willing, to fly most any type of aircraft, although technically he was licensed only as a helicopter pilot.

On the afternoon of July 26, 2003, Laurence was transporting two park rangers, both of whom were wholly unmoved by the sweeping, iconic setting of Grand Teton National Park, on a reconnaissance flight. At that moment, the Grand Teton—the highest peak in the Teton range in Jackson, Wyoming, and a mountaineering classic within the climbing community—was nothing more than the extraordinarily unwieldy scene of a tragic accident.

As Laurence climbed closer to the top of the mountain, the rangers’ thoughts were already whirling around how to reach the victims, what to pack for the rescue, where best to be inserted into the scene. Much of this analysis was weather-dependent. If the pause in the storm held, Laurence would short-haul the rangers straight to the site, an extremely advanced rescue procedure in which rangers hang underneath a helicopter on the end of a rope the length of two basketball courts and disconnect from that line directly onto the mountainside. Short-hauling minimizes a helicopter’s hover time in the air but exposes the rescuer to incredible risk, especially in turbulent weather.

The rangers had received some information from the scene itself, transmitted to the ranger station by cell phone 45 minutes earlier from one of the victims on the mountain. They knew that several climbers had all been struck by a single bolt of lightning just shy of the 13,770-foot summit of the Grand Teton on the Exum Ridge on a 120-foot section of smooth, steep granite known as Friction Pitch.

The rangers were aware that someone in the 13-member climbing party was performing CPR on one of the victims and that there was an array of other burn injuries, including paralysis. They also understood that three of the climbers had hurtled out of sight below Friction Pitch, presumably in a treacherous area of the mountain called the Golden Staircase.

As the helicopter climbed, the rangers searched for figures on or below the brilliant glow of the Golden Staircase, but they couldn’t make out any signs of life. About 100 feet below Friction Pitch, in the midst of a vertical sheer rock face by the Jern Crack, they did see three people clinging to the side of the mountain, their ropes apparently tangled in a few rock spurs positioned just above an abyss.

When they reached the top of Friction Pitch, the rangers were momentarily staggered by the sheer scope of the accident site. There were several seemingly dazed climbers wandering above the pitch, a young man with sandy hair and a vacant expression leaning against a large outcropping of rock, a motionless young woman slumped over the top of the ridge, and, most sickening of all, another figure, whom the rangers would come to call the Folded Man, swinging upside-down from a rope about 50 feet down the mountainside. It was completely unclear to them how far he had fallen or how he had ended up in that location. His body was twisted into a sharp inverted V, the back of his head almost touching the heels of his feet, his belly button skyward. He was utterly still.

Leo Larson, something of a Fabio doppelgänger at six-foot-five and 195 pounds, his long blond hair pulled back in a loose ponytail, calmly snapped a few photos to share with the other rangers back in the rescue cache. Both Leo, age 47, and Dan Burgette, the second ranger in the chopper, had been with the Jenny Lake team before they had even begun using short-haul insertions in the mid-1980s. As the day progressed, Dan’s duty as spotter in the ship would be taken over by Renny Jackson, head ranger, 27-year Jenny Lake veteran, and all-around legendary climber.

The Folded Man remained limp and unmoving, and both Leo and Dan silently began calculating the safest way to recover the suspended body intact. Watching him rotate in the wind, contorted in the most unnatural of positions with no effort to struggle, the rescuers presumed that he was no longer alive. Still, Laurence kept the helicopter stable, lingering in the air about 60 feet away, as they checked to be sure.

Laurence and Leo were on the side of the aircraft closer to the mountain. Laurence, in particular, was transfixed by the man’s torso split in that pose—as he later said, he didn’t realize a body could do that—and he felt a wave of sadness wash over him as he flashed on images of forlorn bodies snarled in ropes and swaying in remote and precipitous regions of the Eiger.

It was while he was lamenting the desperate loneliness of epic mountain deaths that Laurence believed he glimpsed the man’s hand twitch—or else merely witnessed his fingers flutter in a gust of wind. Laurence looked back at Leo and Dan and, in as unruffled a tone as perhaps only a pilot holding a hover at high altitude can marshal, said, “He’s alive.”

“Yeah,” Leo said. “I saw it, too.”

And as simply as that, the mission, at least as it applied to the victim who was hanging, in every true sense, on to his life by a thread, very distinctly took on the heightened urgency of a lifesaving rescue.

Traditionally, in a climbing-related rescue, rangers respond to a single person in trouble. In this situation, the multiple victims alone rendered the operation outrageously complicated, requiring a team of rescuers versed, and secure, in enduring a perpetually fluid and ever-worsening series of circumstances and weather conditions.

In the summer of 2003, the Jenny Lake climbing rangers were faced with several critically injured victims spread over a variety of different locations on the mountain, with turbulent weather, diminishing daylight, and extreme vertical terrain just below the mountain summit. The risk was further ratcheted up with the necessity that the pilot execute precision, high-altitude helicopter maneuvers in the midst of a lightning storm while rangers dangled from the end of a 100-foot rope. Beyond relying on trust, experience, and instinct to execute a flawless—literally flawless—rescue, the rangers would also need every twist of luck to go their way. The chances of the rescuers extricating all of the victims before darkness grounded the helicopter were devastatingly remote and dwindling by the second.

This is the story of the Jenny Lake rangers beating those odds.

* * *

It is a rare thing for a ranger to save a life, even in the world of mountain rescue. Given the violent nature of mountaineering injuries and the remoteness of their locations, most serious accidents are fatal. The rangers in Grand Teton National Park confronted several deaths every summer season. This would, however, be the first time a climber had been killed in the park by a lightning strike.

Leo glanced up at the progress of the storm, the fading light. He and Dan made the briefest eye contact. It was unspoken, but they both knew it would take something damn close to a miracle for their team to pluck all of the victims off the mountain before nightfall. Success would necessitate the most complex and sensational operation ever performed in the park. It would require, in fact, what is widely considered the most spectacular rescue in the history of American mountaineering.

For a frozen moment, Leo looked steadily at Laurence, blue eyes meeting blue eyes, then nodded briskly, definitively, at the pilot. In response, he dipped his rotors and veered down to the Saddle.

TWO

“I get paid to do what other people do on their vacations. Except for the training.”

—

Jim Springer, Jenny Lake ranger

When Renny received the call about the lightning strike on Friction Pitch on July 26, 2003, a Saturday afternoon, he was home with his daughter, Jane, then age 11. It was instantly clear to him from the information in the call-out—multiple patients, CPR in process on one, several missing climbers, bad weather, high elevation—that it was going to be a huge rescue. It was also apparent to Renny that while the mission would require many of the skills that he and his team regularly trained for every day, that particular tangle of events, at that specific time and place, would be anything but routine. In fact, it quite obviously had the makings of a once-in-a-career sort of rescue.

Renny Jackson’s five-foot, 101/2-inch frame is 150 pounds of pure, tightly coiled muscle, ideally designed to allow him to scramble up cliffsides Spider-Man-style. At first glance,

the combination of his wire-rimmed glasses, his slow and soft voice, and his habit of using as few words as possible to make a point makes him appear bookish, lazy, almost timid. By the second glimpse, it becomes apparent that his brand of self-possessed confidence commands not just respect but also unwavering attention. He exercises in a traditional manner less than might be expected for someone with his exceptional core strength—in the winter, off-season for climbing, he lifts the occasional weight, goes for a run now and then, skis in the backcountry—but, as Renny says, the way you keep in shape for climbing is to climb.

And as a Jenny Lake ranger, climb he did—at work, on his days off from work, on vacation from work. Virtually all of his travels are climbing-related. His wife, Catherine, is a world-class climber herself. Family vacations and family traditions revolve around climbing always. His daughter can barely remember a time when she wasn’t climbing with her dad.

When Renny can’t get outside in the mountains, in bad weather, for example, the climbing gym in town, which seems as if it might be beneath him, actually provides some hand routes that are as challenging as climbing gets. Another climbing-centric workout he does indoors is chin-ups, despite the tendonitis in his elbows, to maintain his phenomenal arm strength. He knocks them out while drinking strong coffee and listening to rock-and-roll music. Ideally, he hooks up with another ranger, blares some Bob Dylan or Rolling Stones, and works through what he calls Chinese chin-ups. The pattern is Renny doing 10 of them, then the other ranger doing 10, then Renny doing nine, and so on, until they are each down to one, and then they take turns adding one each time until they get up to 10 again. The end result is that both rangers execute more than 100 chin-ups in rapid-fire speed.

By 2003, Renny had been hauling injured hikers and climbers out of the Tetons for more than a quarter of a century, about half as long as the Jenny Lake rangers had been around. Twenty years before they became the country’s most prestigious search-and-rescue climbing team, the Teton park ranger concept was conceived in 1926, when Fritiof Fryxell came to Jackson to research his doctorate in glacial geology. He returned the next year with his friend Phil Smith to claim first ascents on many of the range’s peaks, and the two of them became the first seasonal rangers when the area became a national park in 1929.

A Bolt from the Blue

A Bolt from the Blue