- Home

- Jennifer Woodlief

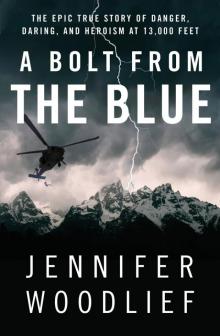

A Bolt from the Blue Page 6

A Bolt from the Blue Read online

Page 6

The rangers wore Nomex flight gloves and carried Nomex balaclavas to protect their heads and necks. The material didn’t keep the rangers especially warm, but most of them stripped off their flight suits after they landed on the mountain and wore regular climbing clothes underneath the Nomex. The underlayer they chose was generally stretchier and easier to move in than the Nomex and also often more wind-resistant and warmer.

After they finished dressing, the rangers began packing up their equipment in anticipation of being flown to the scene: rescue sit-harnesses with extra gear, ropes, belay devices, headlamps, climbing helmets, climbing pants, warm clothes, rescue kits, food and water for one night.

Despite their status as some of the fittest human beings in the country, the rangers did not tend to bring healthy snacks or commercial energy bars on a rescue. For quick sustenance on the mountain, Renny, who despised PowerBars, instead hoarded Caramello and Milky Way bars in his pack. He was not, however, a ready-pack person, so he gathered the combination of snacks and soda he had snatched on his way out the door at home plus junk food he scrounged from the stashes of other rangers. Most of the rangers had a favorite candy bar, and all of them ate various combinations of thrown-together gorp. Veteran George Montopoli, whose first job as a ranger was in 1977, prior to receiving his PhD in statistics, favored pepperoni and jerky for fast calories.

Dan Burgette loved cookies, and over the years of trial and error, he perfected his own cookie recipe that he baked himself and shared with the team. According to Dan, they lasted for years.

Here is Dan’s recipe:

LARGE TRAIL COOKIES

11/2 cups brown sugar

1 cup white sugar

2 sticks margarine

3 large eggs

2 teaspoons lemon flavoring (or vanilla or maple)

3 teaspoons vanilla

1 cup white flour

2 cups whole wheat flour

1/2 cup bread flour

1 teaspoon baking soda

1 tablespoon baking powder

1/2 teaspoon salt

2 cups oats

4 cups any combination of vanilla chips, butterscotch chips, peanut butter chips, chocolate chips, nuts, raisins, M&M’s, dates, brittle bits, or Craisins

The only instructions are to mix the ingredients together, then put baseball-sized lumps of dough on an ungreased cookie sheet and bake at 350 degrees for 24 minutes. The recipe yields approximately 18 (large) cookies.

* * *

While Laurence was in the air, Brandon and the other rangers in the rescue cache flipped a sign on the door reading “Rescue in Progress” and continued coordinating their options, floating potential routes and strategies, monitoring the weather constantly. They used a white board to map out routes, with Jim Springer taking the lead on this, both because he was talented at it and because Brandon’s drawings always tended to turn inadvertently phallic.

Almost every ranger involved in the strategy session (and in the air) had held leadership positions on rescues in the past, and every one of them was qualified to make quick, sound decisions regarding patient care and rescue operations. Laurence, the master of understatement, repetitively used the word “competent” to describe this particular assortment of rangers.

The group dynamic in the rescue cache was fluently efficient, with more listening than talking—everyone threw out his own opinions yet carefully weighed opposing points of view. In coming up with a plan, each ranger had the opportunity to be heard while the others listened intently. The crucial difference from, say, a board meeting was that the whole process spun out in rapid fire.

Wind, altitude, angle of terrain—all of these aspects fed into the enormously complicated decisions they had to calculate as a group. In rescue scenarios, there is frequently an elevated level of what the rangers refer to as objective hazards. In this situation, for example, by putting themselves at the top of the Grand on a summer afternoon with storm cells swirling, there was the very real risk of additional lightning strikes.

On occasion, the rangers themselves have been shocked by ground currents that run through the rock after the mountain is struck. Both Renny and ranger Jack McConnell have been blown off rocks on the Grand by ground current. It’s considered an objective danger for them, and one of the reasons they ideally get an early climbing start is so they are off the mountain when things get, as they say, “sparky” (or, more irreverently, “zappy”). The rangers obviously don’t choose the timing of their rescues, however, a reality that puts them at risk in weather situations they would otherwise avoid.

In hashing out a plan, the rangers raised and evaluated small details, lifesaving minutiae: it’s been warm lately, so watch for rockfall; yesterday there was ice on that pitch. The rangers’ divergent backgrounds were all tossed into the analysis of the mission in varying degrees, sort of like a backcountry think tank, culminating in a finely tuned collective mind-set.

In the midst of this, Brandon was also simultaneously anticipating potential needs about five steps ahead, ordering resources—ambulances, for example—that even in the best case wouldn’t be used for hours.

While they waited for the feedback from the aerial view of the scene, the rangers were in further cell-phone contact with the climbers trapped on the Grand. The husband of the woman who was directly hit by the lightning had a cell phone in his pack, and Bob Thomas called back on that line. The rangers learned that the climbing party was a group of 13 people from Idaho, an extended family and some work buddies from the IT department of a health-care company in Idaho Falls. They had been ascending the Upper Exum Ridge of the Grand around the 13,000-foot elevation when clouds and wind moved in and rain began to fall, and they had abandoned their summit quest less than 800 feet from the top. Members of the group who had summited the Grand in the past were experienced enough to realize that the fastest way down from that point was actually to climb a bit higher, up and around Friction Pitch.

In North America, climbs are assigned difficulty ratings using the Yosemite Decimal System (YDS) (different countries use different rating systems). The goal is to help climbers identify routes that fall within their skill level or that represent the next level of challenge. Climbs are typically rated based on the hardest move, or the crux, of the route, although modern ratings may also take into consideration the overall length and difficulty of a climb. In addition, climbing guidebooks often add an unrelated star ranking to the YDS rating, to indicate a climb’s overall “quality” (meaning how fun or worthwhile the climb is). Although there is an attempt at precision with the YDS rating, climbing standards evolve, and changes in the rock occur over time, so the scale is considered a bit subjective.

The YDS was initially developed by the Sierra Club in the 1930s to classify hikes and climbs for mountaineers in the Sierra Nevada. Before that time, climbs were described only relative to other climbs, and this primitive system was difficult to learn for those who did not yet have experience. The Sierra Club established a numerical system of classification that was easy to learn and seemed practical in its application.

The grading system now divides all hikes and climbs into five classes. The Class 5 portion of the scale is the serious rock-climbing classification. The exact definitions of the classes are somewhat controversial, but in general, Class 1 is categorized by walking on an established trail with a low chance of injury. Class 2 refers to hiking or simple scrambling up a steep incline, with the possibility of occasional use of the hands for balance, with little potential danger encountered. Class 3 refers to scrambling with increased exposure up a steep hillside. A rope can be carried but is usually not required. Falls are not always fatal. Class 4 is simple climbing with increased exposure. A rope is often used. Natural protection can easily be found. Falls may well be fatal. Class 5 is technical free climbing involving rope, belaying, and other protection gear for safety. Unroped falls can result in severe injury or death.

Class 5 was subdivided decimally in the 1950s. The system was d

eveloped by members of the rock-climbing section of the Angeles Chapter of the Sierra Club, and it was initially based on 10 climbs of Tahquitz Rock in Idyllwild, California. The climbs ranged from the Trough at 5.0, a relatively modest technical climb, to the Open Book at 5.9, considered at the time the most difficult unaided climb humanly possible.

By the 1960s, however, increased standards and improved equipment meant that Class 5.9 climbs had become only moderately difficulty for some climbers. Rather than reclassify all climbs each time standards improved, it soon became apparent that an open-ended system was needed, and as a result, further decimal classes of 5.10, 5.11, and higher were added.

To add to the confusion, it was later determined that a 5.11 climb was exceptionally harder than a 5.10, and consequently, many climbs of drastically varying difficulty were bunched up at 5.10. To solve this problem, the scale has been further subdivided above the 5.9 mark with suffixes from a to d.

Current grades for climbing routes vary between 5.0 (very easy) to 5.15 (extremely hard). Further designations of plus and minus are sometimes used to create even more exact ratings.

A breakdown of the Class 5 YDS scale is as follows.

5.0 to 5.4: Very easy climbing with good holds.

5.5 to 5.7: Steeper climbing with good holds. Ropes generally required. This is the upper end of climbs considered suitable for beginning climbers.

5.8: Vertical climbing with smaller holds.

5.9: Route may be slightly overhung with smaller holds.

5.10: Far more technically challenging, possibly more overhung with small holds.

5.11: Steep and difficult routes that require exceptional technique and a high level of strength.

5.12: Very difficult, often professional-grade climbs.

5.13 to 5.15: Extremely difficult climbs considered among the hardest in the world.

The YDS scale rates the Upper Exum Ridge route up the Grand Teton at 5.5. This route, on the south ridge of the Grand, is the most popular way up the mountain.

The Direct Exum Ridge route, which includes the Lower Exum Ridge route, a difficult 13-pitch exposed route, is considered one of the most classic and enduring climbs in North America. The route has long been split into the Lower and Upper Exum Ridge routes. It is common for climbing parties to bypass the more technically challenging lower section and climb exclusively the upper section.

The first ascent of the Grand via the Exum Ridge route was on July 15, 1931, by Glenn Exum, climbing solo, on a day when his mentor, Paul Petzoldt, was busy guiding a couple up the original Owen-Spalding route. The second ascent of the Exum Ridge route was made by Petzoldt, later the same day. Exum and Petzoldt went on to open Exum Mountain Guides that year. Fifty years later, Exum made a final climb of the Exum Ridge route on the anniversary of his first ascent.

Renny Jackson’s guidebook makes the following observation about the route: “There are so many variations available on this ridge that it is possible to make two or three ascents and scarcely touch the same rock twice.” Depending on conditions and the strength (and confidence) of the climbing party, the difficulty level of the climb can vary considerably. More experienced climbers can safely climb most of the ridge with very little belaying, while other climbers may want to belay the whole route.

Other climbing guidebooks generally describe the route with some variant of comments that the rock itself is generally considered excellent and that the sweeping views from the top are magnificent. Reviews and descriptions warn that climbing parties should not expect, especially on a Saturday in the middle of the summer, to have this route to themselves. They also note that a problem with the route is that if climbers become too tired to summit or the weather turns bad, there is no easy way to escape.

To reach the Exum Ridge route from the Lupine Meadows trailhead, where the rangers’ rescue cache is located, climbers hike the trail up Garnet Canyon to the Lower Saddle. There is a fixed rope in the final section to help with the scramble up to the Saddle.

From the Lower Saddle, climbers follow a path north up a gully, where they pass to the left of a smooth pinnacle known as the Needle, a tower most easily reached via a switchback route that involves crawling under a boulder. Ideally, climbers then pass through a tunnel called the Eye of the Needle, but if they miss the Eye, there are other ways through the maze. From here, the ledge of Wall Street can be seen on the wall above.

Above this point, climbers must traverse right, crossing a broad and relatively easy couloir to the start of Wall Street. The beginning of the Upper Exum Ridge route is marked by the giant ascending ledge of Wall Street leading from the gully to the crest of the south ridge. The Wall Street ledge is a wide, slanted ramp that angles up the west face of the Exum Ridge. It slowly narrows as climbers ascend it until it disappears just before the ridge crest. At the very end, the last 10 feet suddenly become very narrow and extremely open to the elements.

Climbers can fall several hundred feet from this point before hitting anything flat. The step-around is the most exposed, intimidating move on the entire route. To get past this corner, climbers have to execute a wide straddle across a gap with 2,000 feet of air between their legs. All but the most experienced climbers rope up in this section.

After that is the Golden Staircase, the second roped pitch, which ascends directly up the ridge crest to a steep, knobby face. It has cracks and lots of knobs for holds, so it isn’t especially arduous climbing, although it is quite steep. Climbers then follow a horizontal section near the ridge crest, bearing right up and under (often icy) rocks to a chute known as the Wind Tunnel. After proceeding through the Wind Tunnel gully and following the ridge up for several pitches, climbers are then led straight to the base of Friction Pitch.

Just 770 feet short of the peak, Friction Pitch is known as the crux, or most difficult part, of the climb. It consists of 120 feet of unprotected sheer, slick granite that is considerably more slippery when wet. The rock is generally smooth and unbroken, and the few cracks for handholds and footholds are particularly thin. The pitch (meaning any distance climbed carrying a standard rope) is so named because in order to scale it, climbers must depend on the friction of their feet against the mountain.

Once a climber has scaled Friction Pitch, summiting the Grand at that point only entails scrambling for two more pitches. Directly above is the V Pitch, one of the most exposed areas of the route, where climbers have to ascend a southwest-facing dihedral (a vertical right-angled corner on the cliff). At that point, climbers continue following the ridge on the Petzoldt Lie-back Pitch, which can be challenging if, as is the case nearly year-round, it is covered in ice. From there, a small 10-foot tower can be climbed directly via a crack, and another 100 feet above that, the ridge becomes broad and nearly level. Then there is just a scramble to the east of the crest to the summit of the Grand Teton.

Once the climbing party from Idaho made the decision not to summit, they began to retreat from their location by scaling Friction Pitch with the intent to rappel down the V Pitch. The first two rope teams (groups of three and four) climbed the pitch and traversed a rubble-covered ledge system to position themselves, after one long rappel, at the start of the Owen-Spalding route down the mountain.

The third three-person rope team was in the process of climbing Friction Pitch, and the fourth three-person team was waiting its turn on the ridge below, when, at about 3:35, a single, colossal lightning bolt struck the Grand.

The strike hit a 25-year-old female member of the climbing party directly, causing her immediately to go into cardiac arrest. The same bolt then fingered out, traveling down the rope and the ridge, pounding through the bodies and convulsing the muscles of the other five climbers on and below Friction Pitch.

Within what seemed a freakishly short time after flying Leo and Dan past the scene on Friction Pitch, Laurence was back with the digital photos Leo had snapped at the scene. On his way down the Grand, Laurence had landed at the Lower Saddle to let the rangers off, then took to the air aga

in to ferry the pictures down to the rescue cache. Brandon displayed the photos on a computer screen for the rangers to view. This was an invaluable extension of the initial size-up by Leo and Dan. Rescuers not yet on-scene could actually see for themselves what they were up against and gain a more complete understanding of the needs at the site.

The visual of the Folded Man dangling in the middle of the rock face, his body bowed grotesquely backward to an extreme angle, sharply illustrated the desperation of his situation to every ranger scrutinizing the photos. He was hanging from his harness on the vertical face on the right side of the ridge just above the crux. It looked as if his back was broken. The rangers were uneasy about how extensively his ability to breathe must have been compromised. The climber obviously had to be critically hurt to remain in that pose without trying to do something to right himself. The photographic evidence of his existence galvanized the priority of getting to this man, of attempting to save him before they ran out of time.

The location of the three climbers who had disappeared off a ledge below Friction Pitch and hadn’t been heard from since remained uncertain. Bob, the climber who made the cell-phone call for help, thought that the three men had fallen down to the area of the Golden Staircase, just above Wall Street. One of the missing men was Bob’s son.

A Bolt from the Blue

A Bolt from the Blue